When I was in the university studying history, we were told to a point of boredom how flawed the Great Men History was. While methodological discussion is always very important, I couldn’t help asking myself then, what the heck lecturers meant by this attack. I didn’t recognise the phenomenon and I felt they were stucked into past decades discourses, into something that was way before my time. History professors stuck in the past, some irony there.

Now that I’m not attached into the academic world anymore I have come to appreciate their point of view more, and I’m taking a liberty of interpreting their meaning to be against history culture, not history students nor academic circles. History culture, or popular history, or representations of history in popular culture, whichever term is now in vogue, is still full of great men history. It’s not that it’s intentional violence against methodology, but popular productions need simple stories that focus into individual, and that’s all you need to lower yourself into the level of great men history.

The great men history means the quite flawed view of history, where historical events and developments are presented to be a consequence of will and actions of one individual, typically a well-born man. Usual hallmarks of this genre are idealizations of individuals, building saints over mortal men, forgetting their flaws or portraying their adversaries as thoroughly evil. Everyone surely agrees that this is wrong.

However, the question is more complicated than just evil Hollywood history vs. academic purity. History is not only facts, it’s interpretation. History is not a science where only facts exist or where the truth can be verified by numbers. History is part of our identity, so it’s also a psychological and cultural phenomenon – a past event can have very different interpretations depending on individual. Take any war for example: when you move on to make a historical interpretation on it, you’ll take a walk in a minefield.

Also it’s a question of the mission, role and meaning of history. Why do we create interpretations on past? What do we want to achieve by it? The ancient historians had a clear answer for this: to teach. There’s also the root of great men history, it originally meant to teach a moral lesson how to live your life and what to learn from the great leaders of past.

Now, for me as a history buff since something like 5 years old, the pedagogic value of history and great men history especially, has been there always. Like the characters of fictional literature, also the individuals of the past have been a source of contemplation, emulation and inspiration to me. A question that has been there ever since my pre-school years has been: why people do the things they do? As a school age kid I enjoyed immensely to read different presentations of great historical leaders. And I especially enjoyed the moments when I found something so compelling from a source I otherwise despised, that I had to update my own opinions. Without those moments I doubt very much I would have taken a life-long interest in history.

So when I went to the university, the over repeated condamnation of the great men history for me felt like the professors were stuck into the contemplations I had solved already in my pre-teen years: surely we were all adults (or thereabouts) as university students and didn’t need to dwell in the obvious: all men are mortal and have their traits seen as strengths or weaknesses depending on the interpreter. In fact, I felt that condamnation of the great men history was counter-productive. I felt strongly, and still do to a limit, that there is pedagogical value, or moral value, in the great men history. If we remove the moral lesson from history altogether, I think we remove a great deal of its value for humanity too. As humans, we have a great ability for abstract thinking and learning lessons from the past, without the need to necessarily make same mistakes again, and we should not waste that talent.

However, and now I’m finally coming to the point I try to make, the history is not just for moral upbringing, it needs its own ethical code as well. For me the prime ethical rule for making interpretations and representations of past is to make justice for the people of the past. The question I ask myself every time I write or speak about the past is that am I making the justice for the past people. Do I understood their view of the world, do I understand their culture, surroundings, their experience of events, their values? And if I do I think I do, then do I manage to translate this understanding in my own representations for my audience in my time and in my culture? Do I do justice to the past individuals as humans?

As a student of Roman noble families, the bulk of people I write about are very little known generally, and for these individuals fulfilling the ethical requirements of this work is quite easy, I don’t need to care about popular images of these people, as there are no such existing. However, the task is considerably more challenging with well-known figures of Roman history, who also tend to be controversial and loaded with meanings, motivations and interpretations of different kinds, piled up during the 2000+ years on these personae. How to approach individuals like Caesar or Pompeius, when whatever I say about them can be seen as taking a stand of some kind, a leaning into one camp of interpretators or another? With these over-used great men of history, the problem is how loaded their images are in the minds of my temporaries.

One problem I face with writing about Pompeius is then that am I writing about Cn. Pompeius Cn.f. Sex.n. Magnus or Pompey the Great? If I’m writing about the Pompey, then I’m writing about an individual, almost like a biographist, trying to find individuality and characterisations of an individual there, or perhaps I’m not writing just life, but life and times, in any case, the focus is on individual and more or less great men history. If I write about Cn. Pompeius Cn.f. Sex.n. Magnus, then I’m writing about an individual member of moderately influental late-republican Roman plebeian family.

With Pompeius this problem of great men history vs. making justice to the individual is markedly present: all seems to hint to that Pompeius didn’t want to conform to be just a typical member of gens Pompeia, or a typical member of Roman upper class. So, while typically one would make most justice (considering the historical individual) to a member of Roman upper class by emphasising the meaning of family networks, as the historical individual would have himself been very aware of the limitations of this cultural setting and conforming to it, one struggles to do this with Pompeius. Pompeius did practically almost everything he could to break free from these limitations and cultural traditions, he was a rebel, and did everything he could to build an exceptional image for himself. To make justice for such a person, wouldn’t great men history approach be ideal? It would represent him in a way he would himself like. However, doing so would also mean to make counter-justice to his family, and to other Roman families as well. This problem is very manifest in countless Pompey-biographies one finds everywhere.

The core of the problem is that Pompeius wished to be, and to be seen, as exception, but in reality he was as deeply tied into the surrounding time and culture as every other Roman was. His own family was as little exceptional as every other family. I’m not saying we should see gens Pompeia as without individual characteristics, but what I’m saying is that we should see Pompey in the setting where Cn. Pompeius Cn.f. Sex.n. Magnus was, as a member of Roman family and its networks, and that we should understand Pompey in the setting of gens Pompeia provided him, not as an idealised or exceptional individual. In this way, we will have both much more deeper understanding of the individual as well as do most justice to the people of the past.

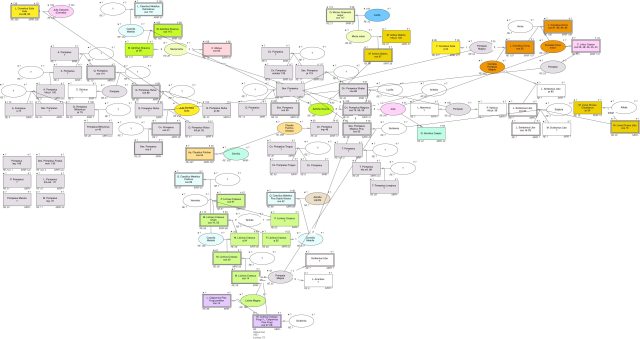

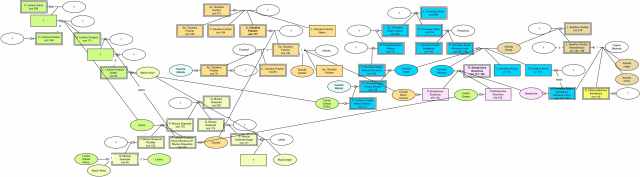

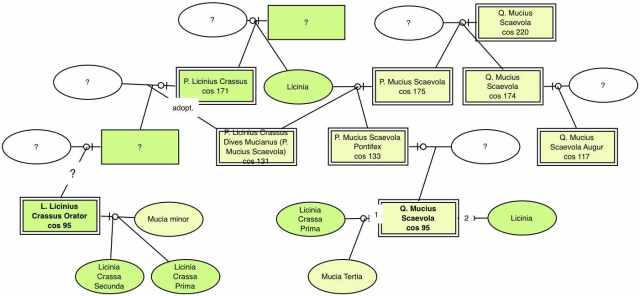

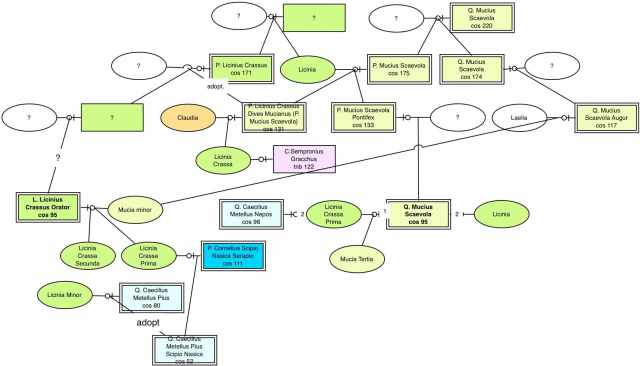

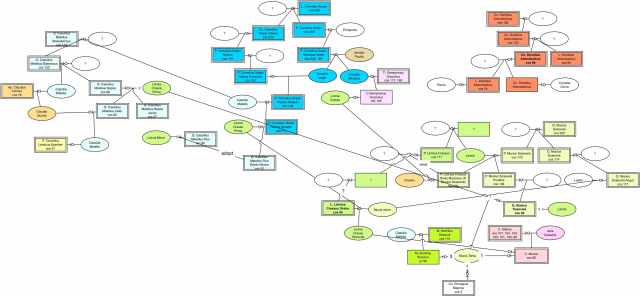

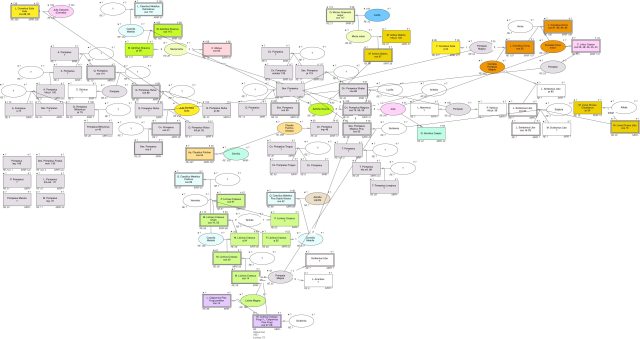

Looking at the family tree of Pompeii during the republican period, one notices two things immediately: there are two main branches of the family, whose common ancestor, should one exist, cannot be traced and that the family on the whole has been active in forming alliances through marriages. The latter note shouldn’t come as surprise as it seems to be tendency of the lesser families to align themselves with more established families through marriages.

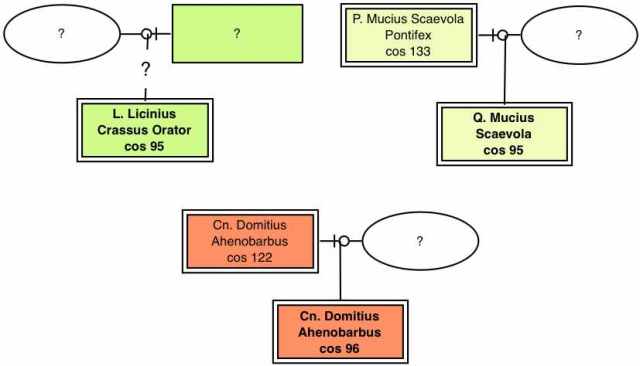

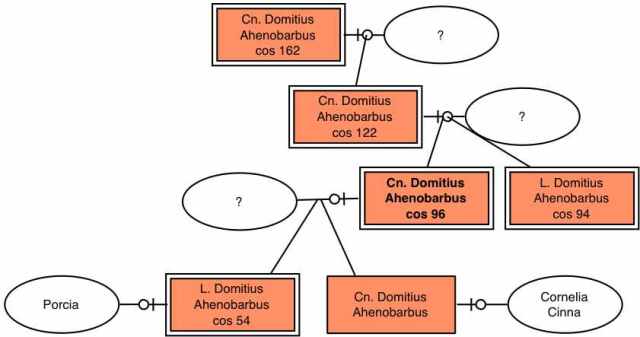

The strong alignment to the party of Sulla is also very evident through the marriage connections. Mucii, Licinii Crassi and Caecilii Metelli are abundantly also present. Also one notices some cumbersome (for us, but probably pretty straightforward for Romans themselves) multi-generational family relationship arrangements.

For example: Pompeius Magnus (cos 70, 55, 52) had a daughter with his wife Mucia tertia. This daughter Pompeia married first Faustus Cornelius Sulla and then L. Cornelius Cinna (cos 32). Cornelia and Cinna had a daughter Cornelia Pompeia Magna, who married L. Scribonius Libo (pr 80), and they had a son L. Scribonius Libo (cos 34). This younger Libo had a daughter Scribonia, who became the wife of Sex. Pompeius Magnus Pius (cos 33). This Pompeius Magnus Pius was of course brother of Pompeia Magna, who married cos 32 Cinna – so we jump some three generations and come back again almost to the starting point.

When we add here the fact that sister of cos 32 Cinna married C. Julius Caesar (the Caesar), who also married a Pompeia from the other branch of the Pompeii, we also get a sense of broader Pompeian family coordination. That makes one presume common ancestor for all Pompeii.

The image of the gens Pompeia starts to emerge where we can find very strong marriage connections to many of the leading families of their era: Cornelii Sullae, Marii, Julii Caesari, Licinii Crassi, Caecilii Metelli, Aemilii Scauri and Claudii Pulchri, within a relative short span of time few decades. While this speaks obviously about the importance of marriage connections, it also raises an observation about the importance of the Pompeii family. If they would have been an irrelevant family, they wouldn’t have managed to build such connections. Shear number of consulships before the Caesar’s civil war is not exceptional, but of course the achievement of three consulships for Pompeius Magnus is exceptional, while added to them there’s only his father consulship and consulships of father-son pair from the other branch of the Pompeii. The Pompeii must have had something valuable to offer for other more established families.

One hint can be found from the life of Pompeius Magnus’ father, consul of 89, Pompeius Strabo. He had won important victories during the civil war and after his consulship (cos 89) ended, he was ordered to disband his armies. However, he was reluctant to do so, and Pompeius Rufus (cos 88) was given order to get the troops of Pompeius Strabo under his command. Strabo refused and eventually was murdered. His son, the future triumvir Pompeius Magnus was also given order of give up his wife and marry according to the command of Sulla. Pompeius Magnus did so as he wad told. The fact was that the Pompeii were useful henchmen of much more important families and got their payment in the form of marital connections and thus growing influence of the family. However, this meant also great sacrifices and loss of freedom of action. I think this is the background one needs to understand about the character of Pompeius Magnus and why he wanted to break free from traditional limits of Roman statesman. One can only guess the pressure he must have felt in conforming the role the family had.

In fact, one perhaps finds same kind of pressure of family position in Pompeius Magnus as one finds in the younger Scipio. Both were obviously very talented, but also very troubled individuals, who were rebels, if not reformers in their setting. Against this background of very strong, if still quite different kind of, family pressure on them, one can find ideas and insights for their exceptional careers and exceptional deeds.