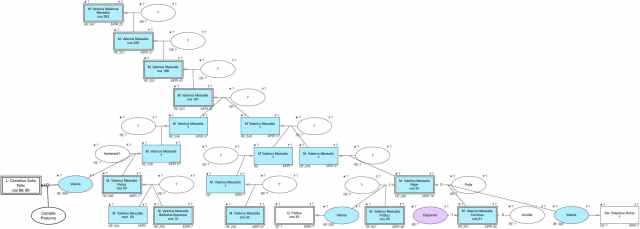

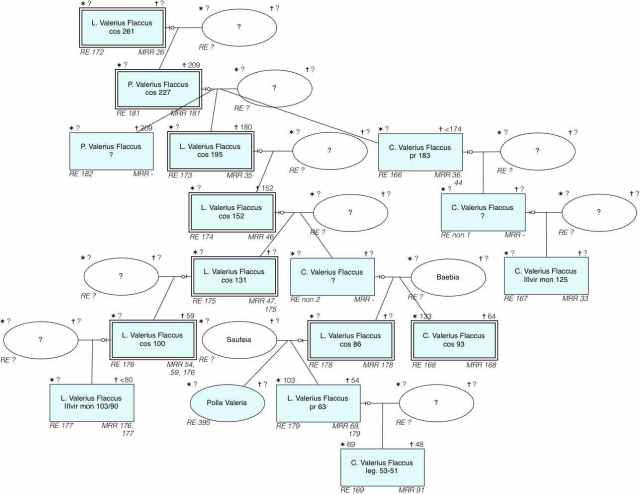

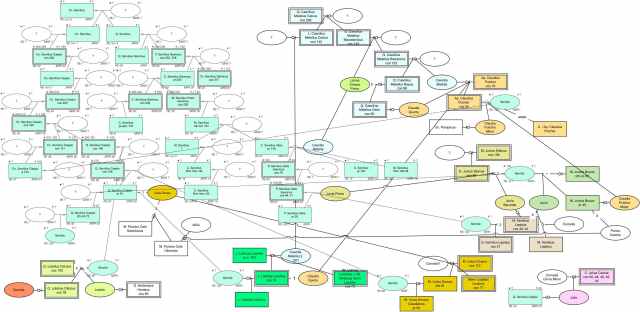

The life and careers of two identically named, but about 130 years apart lived Valerii Flacci are very good examples of what the careers and lives could be in the Roman nobility at the late republic. The consul of 195 L. Valerius was great-great grand father of praetor of 63, so they were from the same direct family line.

A coin by a L. Valerius Flaccus from 108.

L. Valerius Flaccus (cos 195)

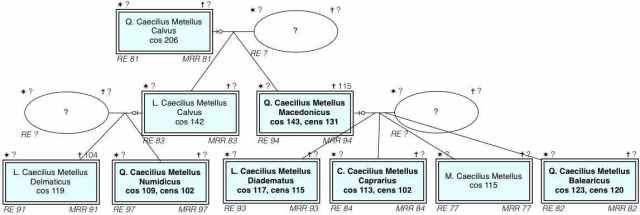

The consul of 195 already belonged into nobility: his father and grand father had been consuls at 261 and 227. Despite this illustrious lineage he was also an open-minded for plebeian contacts, something of which Valerii in general have always been known. His most famous protege, even friend, was M. Porcius Cato (the elder Cato).

The career of L. Valerius expanded for over 30 years:

-Tribunus militum 212, Second Punic War

-Aedilis curulis 201

-Legatus 200, in Gallia under the command of praetor L. Furius Purpurio

-Praetor 199, commanding Sicily

-Consul 195, command area: Italy against invading Gauls

-Proconsul 194, continued consular year command against Gauls in Italy

-Legatus 191, in Greece against Aetolians under the command of consul M´Acilius Glabrio

-Triumvir coloniae deducendae 190 and 189, founded Bologna and supplied Cremona and Placentia

-Censor 184

-Princeps senatus 184

-Pontifex 196-180

Map of the First Punic War.

Valerius met Cato during the Second Punic War and it was a start for lifetime friendship and political alliance, of which more later. In the war itself Valerius took part into important Roman victory at Beneventum, where Romans captured Carthaginian commander Hanno’s camp thus preventing Hanno aiding other Carthaginian troops. However the war that had last up to this point 6 years already would still continue for another 11 years and end only at 201, the year of Valerius’ curule aedileship.

We don’t have a record of Valerius’ offices during the rest of the war, but considering his office as legate of L. Furius Purpurio in Gallia, we might guess that he was not idle. Purpurio had a mission to defend the Roman Gallia against Gallic tribes, but he had only 5000 troops against 40 000 Gauls, who were lead by Carthaginian Hamilcar against the peace treaty with Rome.

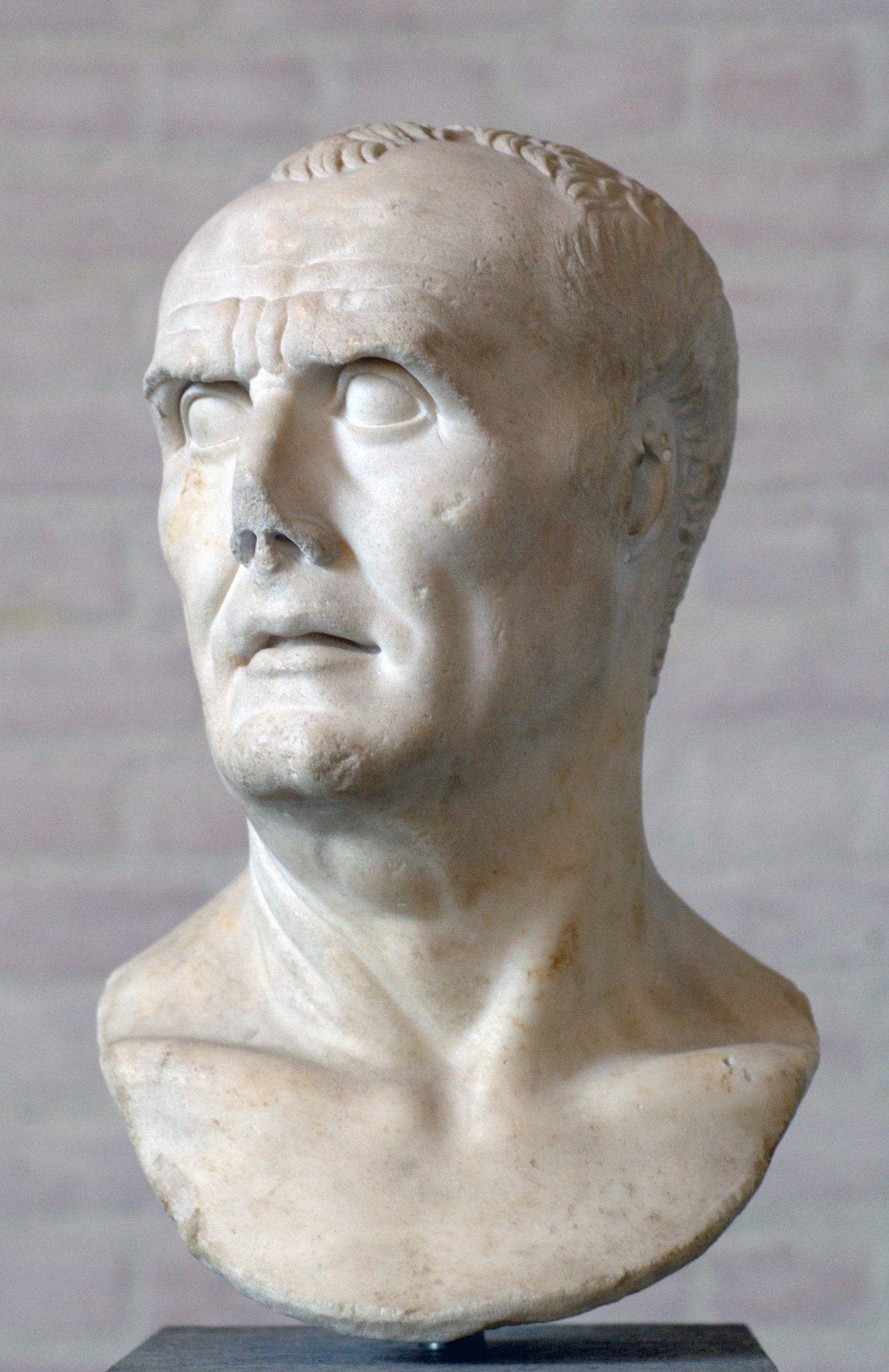

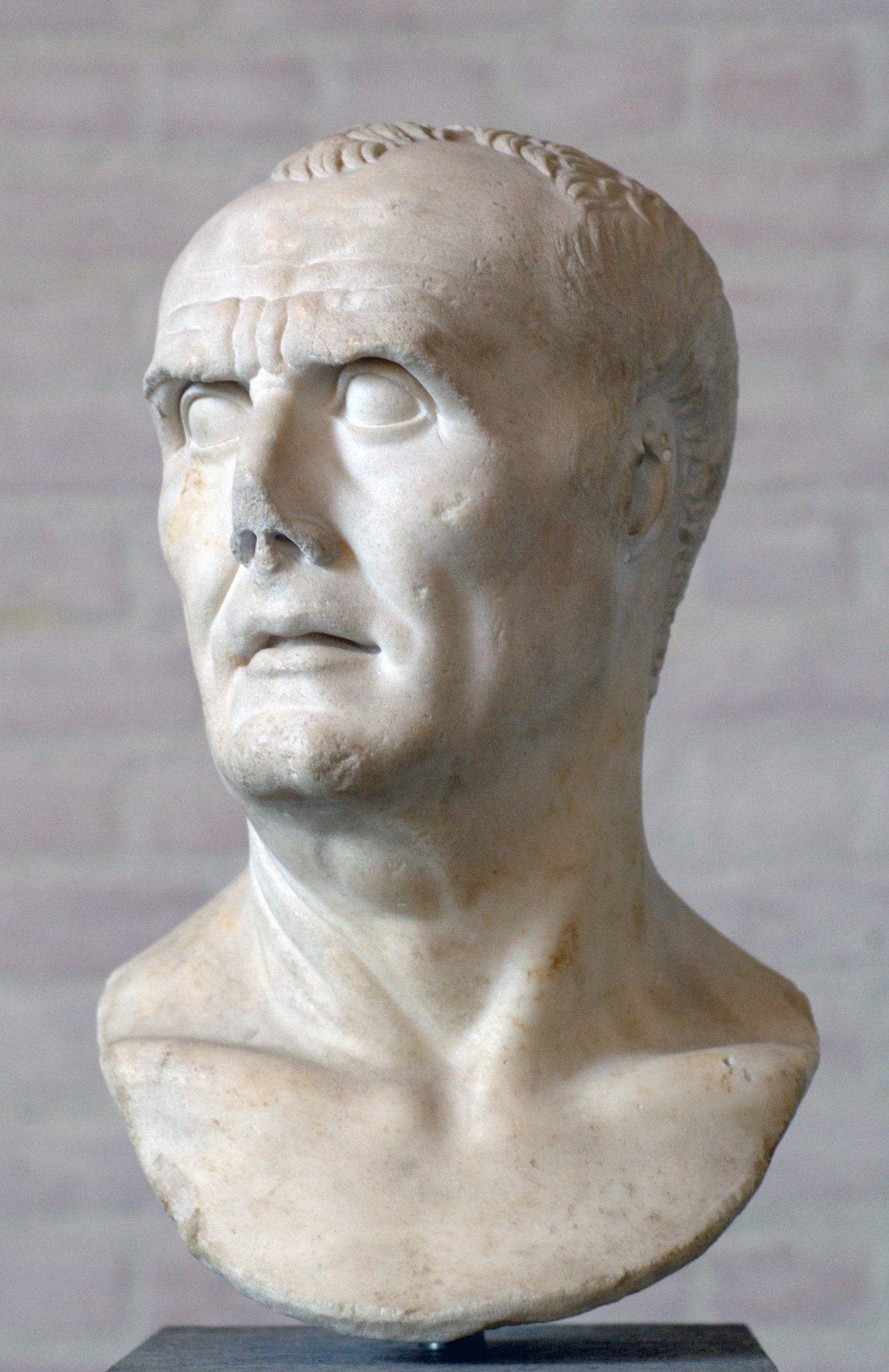

M. Porcius Cato the elder.

Next year, 199, Valerius was praetor in Sicilia and his ally Cato was an aedile. The men shared liking for traditional Roman values against new breed of hellenised Romans like Scipio and Flamininus. Valerius and Cato both supported frugality even to a point of ascetism. Thus 198 Cato as praetor in the province Sardinia followed his ideals and was remarkably frugal in all expenses.

At 195 Valerius and Cato held consulship together and enacted laws against luxury as to be expected. Valerius was sent as commander to protect Italy against invading Gallic tribes and Cato was sent to wage war against Hispanic tribes. Valerius continued war against Gauls also as proconsul after his consular year.

The next command for Valerius was under consul M’ Acilius Glabrio and this time too, Cato was there. Both men were present at the battle of Thermopylae, where Roman forces achieved a devastating victory over Antiochus III of Seleucids and the Roman commander Glabrio gave Cato the credit of the decisive maneuver as of result of which the Greeks decided to flee from the battleground.

Antiochus III of Seleucids.

After these military missions Valerius served as member of three men commissions of first strengthening the Roman colonies of Placentia and Cremona and then to establish Roman colony of Bononia (Bologna).

After couple of years during which we have no record of either Valerius or Cato holding a public office we see them winning the elections for censor for term starting at 184. This most dignified of Roman public offices was a Roman peculiarity. They were in some matters below of even praetores in rank, but still fully independent within their own office and the office was regarded as sacred. Added to census the public moral was their regimen.

One could say that Valerius and Cato were obvious choices from their generation for this special office: both being stern moralists and very conservative in their views. Their censorship indeed is still famous (or notorious, from another perspective) of the severity. It can be said that their censorship was a conservative reaction against the deep changes happening in Roman society after frist Punic Wars. Valerius and Cato expelled many notable men of their time from the Senate and imposed tight restrictions against luxury.

Censorship was the last office Valerius and Cato shared. Cato was younger than Valerius and continued being active in the society without ever having any public office anymore. He continued to have great influence due his remarkable career and personal qualities. Valerius still had one public office to climb. He was appointed as princeps senatus at 184.

Princeps senatus was the first speaker in Senate and while having no imperium (command authority), the post was regarded as ultimate honour that a Roman statesman could achieve. Usually one had to have been both consul and censor, have a long career in politics and to be generally respected amongst senators. The power the office holder had was very political in nature: he was to have first speech in all matters and this way princeps could have great influence in tone and contents over all ensuing discussion of the matter in the Senate.

Valerius was first of his family line to achive this dignified position and indeed there was only one other, L. Valerius Flaccus (cos 100), his great grandson, who achieved this position from their family. Valerius died at 180 as one of the leading statesman of his era.

In the life and career of Valerius we can see many many typical Roman attributes of the era.

His career was like a model of ideal Roman career of military commander statesman, who took succesfully part into the great wars of his times.

Valerius was also an ideal conservative Roman, frugal, stern but just, respected also by his opponents.

We can also see typical Roman way of strong personal alliances in his career. Sharing of several magistracies is far from atypical in Roman system, where one needs strong allies to win elections. Valerius choose Cato as his ally and this obviously was a very successful choice, Cato being able to gather great support from different groups and individuals.

Also e.g. Valerius’ legateship under L. Furius Purpurio in Gallia in year 200 bore fruit five years later as Purpurio was consul in 196 and thus responsible for the elections of consuls of 195, where Valerius and Cato were victorious. This too is typical pattern in Roman politics: the current consuls had great influence in the outcome of the elections for next year and we see many alliances between families working this way.

Valerius was also the leading member of his family and raised it even higher into nobility than his consular ancestors had done. He is third generation consul and there was to be three more generations of Valerian consuls after him, which is a rare achievement for Roman family.

Valerius was born in the decades after the First Punic War and lived his early adulthood during Second Punic War and this era with its very cruel wars probably had a great influence on how Valerius saw life in general and shaped his conservative views further. He belonged into generation of Roman military commander statesmen and while we know little of his private life, he was probably idolised also inside his family, if for nothing else, then being first princeps senatus of his family.

The life and times of his great-great grandchild L. Valerius Flaccus, praetor of 63, were very different.

Rome and Carthage at the beginning of the Second Punic War.

L. Valerius Flaccus (pr 63)

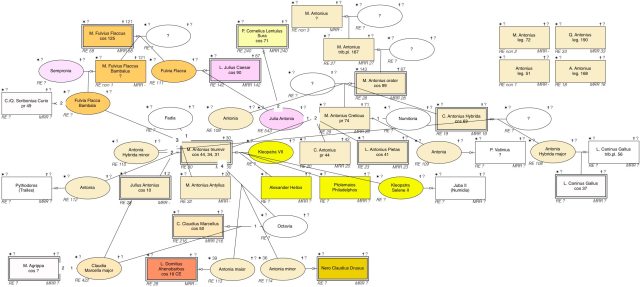

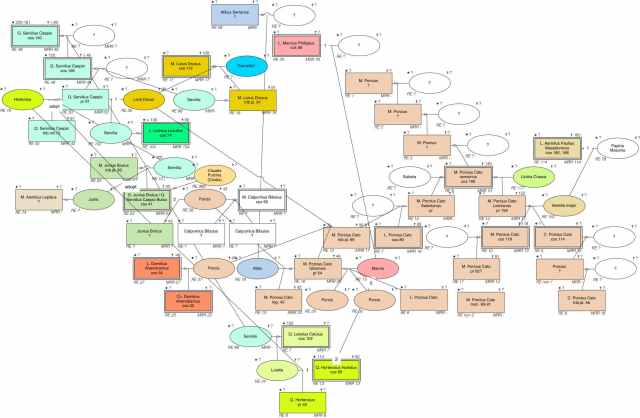

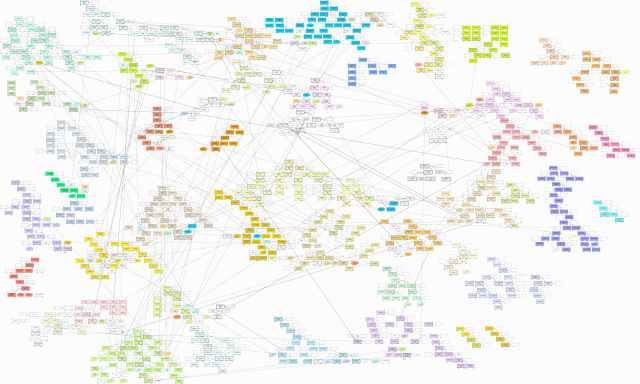

The father of this younger Flaccus was the consul of 86 and belonged to last golden generation of Valerii Flacci. Valerius Flaccus, consul of 195 above, had one son, consul of 152, who in turn had two sons, consul of 131 and another rather unknown son. Son of consul 131 was to become consul at 100 while his cousins, the two sons of otherwise unknown C. Valerius Flaccus mentioned before, were to become consuls at 93 and 86. Younger, consul of 86, was father of our younger Flaccus. So with 7 generations of consuls, with three consuls in his fathers generation, there must have been an enormous pressure for young Flaccus to match the success of previous generations.

C. Marius.

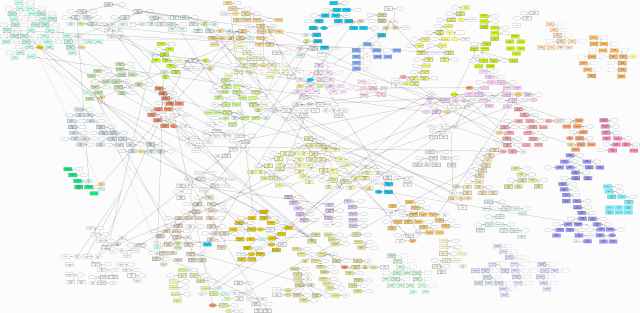

To understand his life we need to first take a look into his father’s career. His advance in the cursus honorum was typical of Roman of his status. He was a military tribune at year 100, when his uncle was consul with C. Marius (his sixth consulship). He then proceeded to be elected as aedile and praetor. He was designated with one of the most richest provinces, Asia, and this can be taken as a sign that Valerii Flacci were strongly allied with Marius and his followers. He also continued his term as propraetor of Asia after praetorship.

It is possible that father Flaccus was also the commander of a cavalry unit near Rome in Ostia, which switched sides to Marius at 87 during the civil war between Marius and Sulla. In any case father Flaccus was elected as suffect consul next year when Marius died shortly after beginning his seventh consulship. Father Flaccus was faced with debt crises right away, with Rome’s economy in danger to collapse. He ordered immediate 75% write off of the debt (both private and government) and the financial situation eased considerably.

L. Cornelius Sulla Felix.

During his consulship Sulla was gathering strength in the east. Father Flaccus and his consular colleague Cinna decided to respond into Sulla’s diplomatic and military build up and Flaccus was sent to the province of Asia with two legions. His son (our praetor of 63) was with him. The campaign was ill-fated. Not only heavily outnumbered by Sulla, but also suffering from storms, and not nearly all of the troops even reached the area.

Father Flaccus’ elder cousin (consul of 100) was declared as princeps senatus and his policy was to try to find a solution to start negotiations with Sulla, if possible. One of the great mysteries we have about the Valerii Flacci family is that shared father Flaccus his cousins’ point of view in this. It might be, as otherwise it is difficult to find a motivation for events of winter 86-85. Then father Flaccus’ sub commander C. Flavius Fimbria mutinied and killed father Flaccus. Fimbria was a devout Marian, so his motivation could be to prevent Flaccus from negotiating with Sulla. A slight support for this theory also comes from the fact that while Flaccus was in command, Sulla did not commit into decisive battles against his troops.

In any case the death of his father in Asia was one of the defining moments of young Flaccus’ life. He was under 20 years old, on his first military campaign, and when his father was killed in mutiny, he had to flee for his life. Flaccus fled into his uncles (cos 93) camp in Gallia. His uncle was one of the strongest men at this time controlling both Gallic and Hispanic provinces.

The start of the official career of younger Flaccus then was under exceptional circumstances of Sullan-Marian civil war. It was also to be continued in similar vein with both of his powerful relatives, princeps senatus (cos 100) and uncle (cos 93) switching sides to Sulla. The murder of his father may have accelerated the run of events, but there are indications that both elder Flacci were already turning their allegiance into Sulla. Younger Flaccus in any case served in his uncle’s force in Gallia as military tribune still in 82.

With Sullan reforms of the state and Roman society returning into normal state of affairs, also the career of younger Flaccus was steered into more traditional direction. He served as military tribune also in Cilicia under Servilius Isauricus. At 76 he was a member of special commission of three to aquire surviving Sibylline books. He was elected as questor for 70. During his quaestorship he was sent into Hispania to serve with M. Pupius Piso and also got prolonged proquaestorship for 69 there. After this is immediately served as legatus during 68-66 in Crete in the forces of Caecilius Metellus (future Creticus).

As consul for 69 and proconsul 68 Metellus took up command against the Crete. Crete had been supporting king of Pontus Mithridates against Rome and also sponsoring several pirates of the area, which were great nuisance and even a danger for Rome. Metellus started a succesfull offensive and captured several Cretan cities. At the same time Pompeius had been given an extra ordinary mission against the pirates at whole mediterranean and was also making progress. The Cretans saw an opportunity themselves and declared surrender for Pompeius, not Metellus. Probably they believed to achieve more lenient terms of peace from Pompeius, for whom Crete was just one pirate base, whereas for Metellus Crete was the whole of his command. The plot was at first successfull and Pompeius accepted Cretan surrender and even ordered Metellus to leave the island with his troops. Metellus however declined and continued the war and swiftly subdued the whole island and declared it as province of Rome.

Cn. Pompeius Magnus.

Traditionally Metellus should have recieved a triumph for his victory, but Pompeius managed to prevent it until 62, when Metellus was finally a triumphator and recieved also cognomen Creticus. Metellus got his revenge by delaying the Senate approval for Pompeius’ reorganisation of Asia after pirate war until year 60.

We can only guess what Flaccus thought about these internal strifes between Metellus and Pompeius, but perhaps a hint can be taken from the fact that after two years with Metellus in Crete at 68-67, he took a post as legatus in Pompeius’ troops in Asia for 66-65 in war against Mithridates. His colleague there was Caecilius Metellus Celer who was distant relative (Creticus’ grandfather was great-grandfather of Celer). This Celer, btw, is famous of being Clodia’s husband and was probably eventually poisoned by Clodia at 59).

In any case after his legateship in the Pompeius’ troops Flaccus campaigned succesfully for praetor and was elected as such for the year of 63. We can safely assume that this was because of the support from Pompeius. It was Pompeius’ method to raise his supporters into power and advance his own career in this indirect way. At 63 we also see Cicero as consul, and he was also sponsored by Pompeius. During his praetorship Flaccus naturally was involved as chairman of the court in the Catilinian conspiracy and probably as payment for his services recieved rich province of Asia as his propraetorian appointment after consulship.

Flaccus was accused of embezzlement of funds after his term of propraetor and was defended in the court by Cicero and Q. Hortensius, the two most prominent public speakers of their era (Ciceros’ speech is known as pro Flacco). The charges were dropped, but there is no doubt of Flaccus’ guilt. In fact, Flaccus is usually held as most obviously guilty of all Cicero’s defence cases, Asia was in poor shape after Flaccus. Cicero knew this fully well, as his own brother followed Flaccus as propraetor of Asia. For Cicero a complication in the trial was that his brother would be facing same sort of trial (for good reasons too) when he would return from the province into Rome. Perhaps one should however give credit to Cicero in geniousness in the way he managed to successfully to defend Flaccus but also leave some ammunition of eloquence for the coming defence of his borther!

M. Tullius Cicero

For some reason Flaccus did not manage to gather enough support to be elected as consul in the coming years. Certainly he didn’t lack illustrious name nor probably money to run a successfull campaign, so probably the reason was that he didn’t have the final support from Pompeius, whose attention was directed into forming of the first triumvirate. Pompeius married Caesar’s daughter Julia in 59. Julia died in childbirth at 54 and the two men were drifted into civil war at 51.

Flaccus was sidetracked from the top political posts during this time and served as legatus of L. Piso in Macedonia in 57-56. Piso was consul of 58 and Cicero’s enemy: he allied with Clodius to have Cicero exiled, which was successul. Piso was rewarded with province of Macedonia for 57-55. Piso was also the father of Calpurnia, wife of Caesar. We know him also as probable owner of Villa dei Papiri at Herculaneum. In any case Flaccus served with him in Macedonia until the recall of Piso because of the influence of then returned Cicero. Perhaps we can see Flaccus selecting Piso as a sign of leaving the Pompeian camp.

Flaccus accepted a command in Crete for 54, but died shortly after. His son was about 25 years old at this time and served as legate in the troops of Ap. Claudius Pulcher in Cilicia at 53-51, but died at the battle of Dyrracheum in 48 at the side of Pompeius. This son of Flaccus was the last Valerius Flaccus.

Republican era provinces of Rome at 78.

The life and career of L. Valerius Flaccus (pr 63) was then much different than his great-great grand father, consul of 195. Even though there was only 130 years between them, the Rome could hardly have been more different. The Rome of elder Valerius was Rome that was struggling with Carthage for the mastery of middle Mediterranean area, relatively small and poor power. Rome of younger Flaccus was rich beyond imagination and having more dangerous internal enemies than any real external enemies.

Elder Valerius knew all his life who the enemy is, and sought to restore traditional values. Younger Flaccus switched sides, witnessed the struggle between Marius and Sulla as well as the rise of Pompeius. Elder Valerius was known for his frugality and stern justice, the younger Flaccus for his embezzlement of provincial funds.

Both elder Valerius and younger Flaccus still belonged into highest circles of Rome. Both knew personally the great men of their time and were friends and enemies with them. Both also had their not small role in shaping the history of Rome, even history of world. Elder Valerius saw his house to rise into highest prominence in Roman politics, whereas younger Flaccus never reached consulship and all but saw the end of his line and house of Valerii Flacci.